Zoogle

Redesigning a game to make it safe for all ages

In my methods for human factors class, I was tasked with designing a game for children ages 3 to 5. For this project, I chose to redesign Zoogle, a game I played during my teenage years at summer camp, adapting it to be safer and more engaging for young children.

In the original version of the game, players threw a stick back and forth, with the goal being to catch it by the handle. If you missed, you would first lose the ability to catch with one hand, then be forced to stand on one leg for the remainder of the game, and finally, you would be out until the next round.

Clearly, the materials used—wood—and the vestibular demands of the game made it too dangerous and complex for young children in my assigned demographic. My task was to redesign Zoogle to make it safer, less physically demanding, and more accessible for children ages 3 to 5.

I began my process by interviewing my younger cousins, ages 6 to 8. While not strictly within my target demographic, they provided a close enough stand-in for my research. My questions focused on how they engaged in play, what toys they used, and why. One interesting finding, which I hadn’t initially considered but later incorporated, was the possibility of cooperative Zoogle rather than a competitive version. I also discovered that my cousins' favorite toys and play often mimicked adult actions.

These findings led to two key insights for my redesign: first, the potential for cooperative gameplay, and second, the importance of matching the game’s complexity to the children’s cognitive abilities. While the goal was to make the game safer and easier, it was equally important not to oversimplify it, as the game still needed to provide meaningful engagement.

My research continued with a Qualtrics questionnaire sent to former campers and colleagues from summer camp, asking for their opinions on adapting Zoogle for young children. One key finding from this step was that the vestibular demands of the original game—such as losing the use of one hand or foot—would be too much for children in the target age group. As a result, I needed to identify a new mechanism for determining how children would win or lose the game.

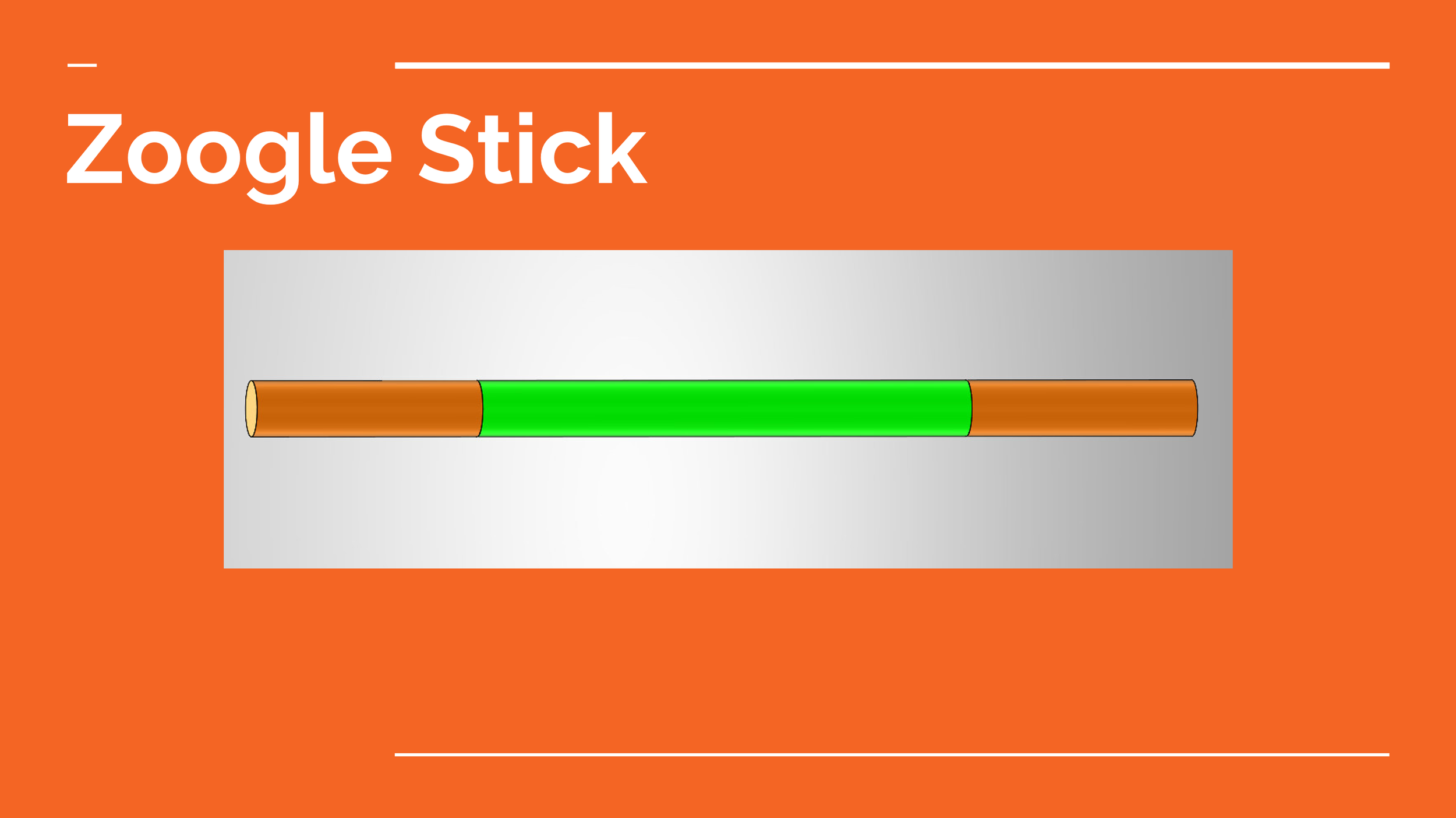

As I continued brainstorming the rules for the new game, I shifted focus to prototyping the toy itself. My two main considerations were the anthropometric specifications—ensuring it was easy for children in the target demographic to hold and throw—and whether keeping the form factor vertical was the best choice.

Based on the 5th percentile for hand length in 5-year-old females (10.8 cm), I designed the circumference of the Zoogle Stick handle to be 10.8 cm. This decision ensured the handle comfortably fit even children in the target demographic with smaller hand sizes. I also reviewed fist breadth anthropometric data to inform the handle's length. Although doubling the 95th percentile value (7 cm) would have accommodated children with larger hands, I opted for a significantly larger handle to provide more affordances for children during play.

I created two form factors for the Zoogle Stick. The first was similar to the original toy—a long vertical stick—but with a significantly larger handle. The second was a circular Zoogle Stick. During testing, I quickly discovered that the round form factor didn’t work, as any rotation introduced made catching it on the handle a game of chance, even for adults. As a result, the vertical form factor was selected for the final product.

I revised the rules multiple times during the development process. Initially, I experimented with a point system to determine winners, but user testing revealed that the game’s fast pace made it difficult to accurately track points. Ultimately, I decided to emulate the game H-O-R-S-E by using the letters Z-O-O-G-L-E, which allowed for fast-paced play while still being easy for players to track their own status.

I also developed a cooperative version of Zoogle, where players toss the stick back and forth in a circle, aiming to see how many successful catches they can make in a row without dropping the stick or missing the handle.

With the toy and game finalized, my next step was to wireframe an app in Figma to serve as a guide for parents explaining the game to their kids. I recruited friends and family for user testing, asking them to complete tasks such as navigating to specific pages.

After incorporating their feedback and refining the wireframe, I conducted a heuristic evaluation of the app, identifying two key areas for improvement: the need for greater visibility of system status and more flexibility through additional inter-connected pages.

Through this project, I successfully applied human factors principles to redesign Zoogle for young children, ensuring both safety and engagement. By considering key aspects such as anthropometrics, game dynamics, and user feedback, I created a toy and game that met the developmental needs of children ages 3 to 5. This iterative design process, from prototyping to app wireframing, reinforced the importance of understanding user needs, testing, and refinement in creating products that are both enjoyable and accessible.